Introduction

I optimized the function Math.hypot to about 200% in v8 which is the javascript engine of Chrome, NodeJS runtime.

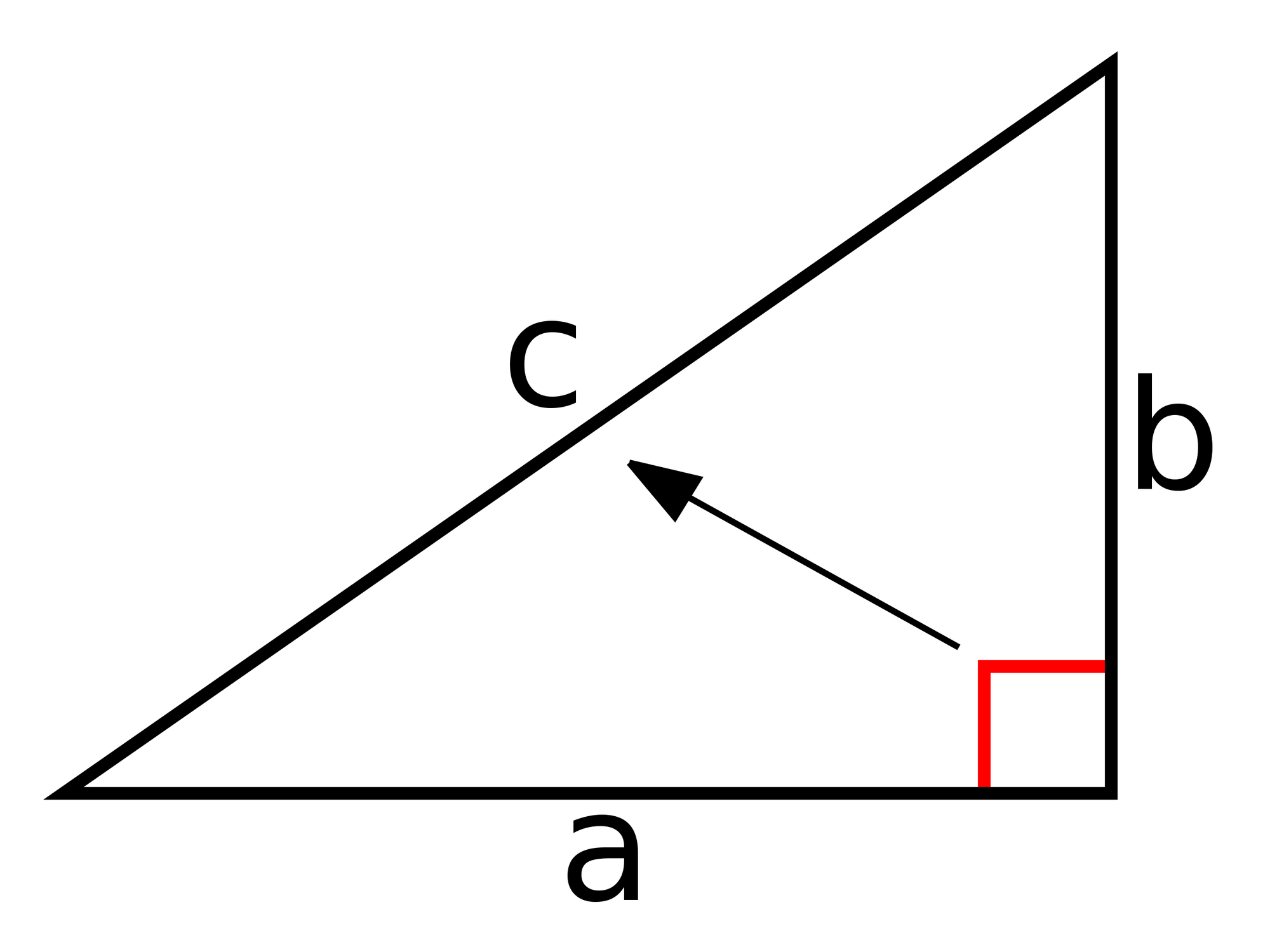

Math.hypot is the function to calculate the distance commonly.

Hypotenuse = C

In this post, I’ll introduce the hypothesis to resolve this losing performance issue, why it was slow, and how to resolve it.

CL: https://chromium-review.googlesource.com/c/v8/v8/+/5329686

Timeline

Explored the issue

While investigating the V8 issue list, I discovered an issue that describes calculating hypotenuse by Math.hypot is 10x slower than implementing by multiply operation. The initial question was why it is notably slow using Math.hypot than other built-in functions like Math.pow or **.

The issue includes the following code snippet used for benchmarking:

const n = 100_000_000

const methods = {

'*': (a, b) => Math.sqrt(a * a + b * b),

'hypot': Math.hypot,

'**': (a, b) => Math.sqrt(a ** 2 + b ** 2),

'pow': (a, b) => Math.sqrt(Math.pow(a, 2) + Math.pow(b, 2)),

}

Object.entries(methods).forEach(([name, method]) => {

let a = Math.random() * 3, b = Math.random() * 91.3, c = 1

let s = performance.now()

for(let i = 0; i < n; i++){

c += method(a, b)

}

console.log(`${name} took ${performance.now() - s}`)

})

And result:

| Method | Runtime |

|---|---|

| * | 103.292ms |

| hypot | 1584.417ms |

| ** | 664.958ms |

| pow | 666.458ms |

You can find the result of Math.hypot slower than *.

Examining the implementation

The Math.hypot function is implemented in torque language and placed, src/builtins/math.tq.

Torque is the language which has a typescript-like syntax used in V8 to implement built-in functions.

// ES6 #sec-math.hypot

transitioning javascript builtin MathHypot(

js-implicit context: NativeContext, receiver: JSAny)(

...arguments): Number {

const length = arguments.length;

if (length == 0) {

return 0;

}

const absValues = AllocateZeroedFixedDoubleArray(length);

let oneArgIsNaN: bool = false;

let max: float64 = 0;

for (let i: intptr = 0; i < length; ++i) {

const value = Convert<float64>(ToNumber_Inline(arguments[i]));

if (Float64IsNaN(value)) {

oneArgIsNaN = true;

} else {

const absValue = Float64Abs(value);

absValues.floats[i] = Convert<float64_or_hole>(absValue);

if (absValue > max) {

max = absValue;

}

}

}

if (max == V8_INFINITY) {

return V8_INFINITY;

} else if (oneArgIsNaN) {

return kNaN;

} else if (max == 0) {

return 0;

}

dcheck(max > 0);

// Kahan summation to avoid rounding errors.

// Normalize the numbers to the largest one to avoid overflow.

let sum: float64 = 0;

let compensation: float64 = 0;

for (let i: intptr = 0; i < length; ++i) {

const n = absValues.floats[i].ValueUnsafeAssumeNotHole() / max;

const summand = n * n - compensation;

const preliminary = sum + summand;

compensation = (preliminary - sum) - summand;

sum = preliminary;

}

return Convert<Number>(Float64Sqrt(sum) * max);

Hypothesis 1: Memory Allocation

Initially, I thought the repetition of memory allocation could increase the memory management overhead.

To test this hypothesis, I modified the implementation to directly use arguments instead of the memory allocation (AllocateZeroedFixedDoubleArray).

However, the performance has not increased dramatically.

Hypothesis 2: Cost of ToNumber_Inline

According to the ToNumber spec, It handles various cases to convert the number or not. I assumed that ToNumber_Inline can be slow if it deals with broad cases.

To test this hypothesis, I modified the code to check the Number type and forcibly cast using UnsafeCast to Float64 instead of ToNumber_Inline.

The result of testing said the performance improvement is 0.5 ~ 2%. Hence, this hypothesis test did not yield a significant improvement.

Hypothesis 3: Cost of Extra operations

The implementation contains hypotenuse calculation and, moreover, extra operations like the Kahan summation algorithm. I hypothesized that the extra operations have cost.

To test this hypothesis (for simple testing), I added a case to the original implementation that calculates sqrt( a ^ 2 + b ^ 2) for only two of the arguments.

if (length == 2) {

let max: float64 = 0;

const a = Convert<float64>(ToNumber_Inline(arguments[0]));

const b = Convert<float64>(ToNumber_Inline(arguments[1]));

if (a == V8_INFINITY || b == V8_INFINITY) {

return V8_INFINITY;

}

max = Float64Max(a, b);

if (Float64IsNaN(max)) {

return kNaN;

}

if (max == 0) {

return 0;

}

return Convert<Number>(

Float64Sqrt((a / max) * (a / max) + (b / max) * (b / max)) * max);

}

The result was surprisingly fast.

| Method | Runtime |

|---|---|

| * | 104.041ms |

| hypot | 814.667ms |

| ** | 670.709ms |

| pow | 674.583ms |

I wanted to test this hypothesis simply so the argument length checking statement occurs.

In an attempt to identify the extra operations that are the reason for this slowness, I removed them from the code below. However, the test result was slow again. Therefore, the “removing the extra operations” hypothesis isn’t valid.

Analysis: Why It Was Faster?

I observed the happening of optimization. If I explain why, I might consider opening a CL(like a PR in Github) for this optimization.

The primary distinction from the original implementation is in the ‘for-loop’.

On the high probability of identifying the suspected ‘loop’, I conducted a test by adding the following code to Math.hypot:

for(i = 0; i<length; i++) {

}

With this, the 200ms latency occurs. Consequently, I formulated two hypotheses to investigate this happening.

Hypothesis 4: The torque loop is slower than CSA’s?

This hypothesis was an idea that “the loop statement in CSA(Code Stub Assembler) compiled from torque is slower than directly implemented with CSA”

As occasionally implementing assembly language can be a valid option for performance, I tested this hypothesis by implementing Math.hypot using CSA. The results showed a slight average speed improvement.

However, the difference is very tiny. Hence, this test result is considered a failure.

Hypothesis 5 and Conclusion: The Hidden Cost of the Loop

This conclusion is from the thinking of what does loop has.

The loop has hidden costs.

There are compare operations when entering the loop and checking for escape N times. So there are N + 1 times of compare operations exist. Also, increase has N times.

Back to the implementation of Math.hpot, There are two loops, leading to a consumption of 6 comparisons and 4 increments. The execution was slow because of the N * 6 comparisons in N times of executions.

Optimization

Therefore, I optimize this by executing when the parameter count is less than equal to 3.

try {

return FastMathHypot(arguments) otherwise Slow;

} label Slow {

const length = arguments.length;

// ...

You can find the full implementation of FastMathHypot here.

Conclusion

Following is the execution result table:

| Method | Runtime |

|---|---|

| * | 104.041ms |

| hypot | 814.667ms |

| ** | 670.709ms |

| pow | 674.583ms |

There is about a 194% performance enhancement, reducing the execution time from 1584.417ms to 814.667ms.

Throughout this optimization, I progressed through hypotheses on memory allocation, ToNumber, extra-operations, and the for-loop. I identified the correct hypothesis and the reasons behind the performance improvement. Finally, I enhanced v8 by removing the overhead from the loop.

We can learn something from this optimization that we should think about the loop’s overhead. Sometimes, the overhead can be more significant than the problem we aim to solve.

At last, Thanks to “Hyunyoung Kim” who reviewed this Korean-version post.